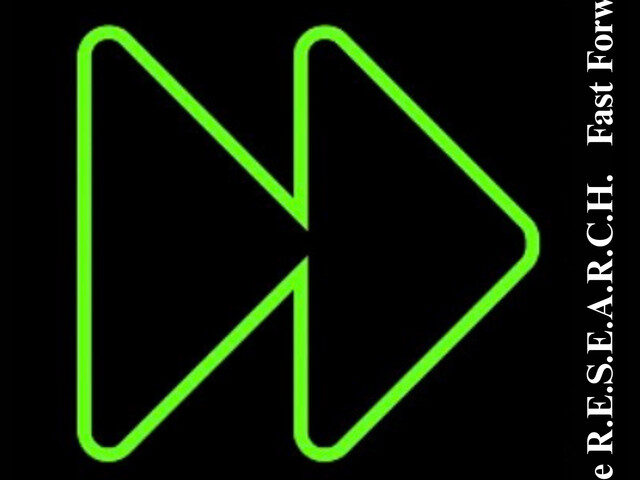

We sit down with Swiss multi-genre composer Alf Jetzer, whose recent album UNFOLDING caught our ears with its masterfully layered textures and cinematic depth. He details his intricate “musical painting” techniques and the deep-rooted meditative practices that allow his compositions to breathe with such singular life.

UNFOLDING feels deeply cinematic and transportive, blending guitars with duduk, udu percussion, singing bowls, and more. When beginning a new composition, do you first envision a sonic “landscape,” or do the textures reveal themselves gradually during the process?

I don’t imagine a landscape. The whole thing is process-oriented. By immersing myself deeply in the individual instruments and the phrases I play on them (making them my own), this expressiveness emerges, which then creates images in the listener’s mind. These images are different for everyone, depending on their individuality.

You’ve described your approach as “musical painting.” When working on a track like “There was a Time,” how do you decide which instruments become the foreground colors versus the subtle background brushstrokes?

The fact is that, measured in terms of its inner substance (energy), every instrument could play a leading or background role. The placement in the room takes place during the process. Towards the end, I can also hear where a few fine “brushstrokes” are needed. It is important that everything is very well coordinated at the end.

Many of the songs balance hypnotic percussion with slowly unveiling instrumentation — particularly on “Zeitgeist.” How do you maintain that sense of patient evolution without losing momentum or emotional pull?

This is something that has to do with my whole way of life, with years of meditation and internalization. It’s not about constantly playing something new to create variety, but about making what already exists even stronger (expressiveness).

Whereas it used to take 100 notes to convey a certain power, today it can be done with just a few notes. So it has more to do with inner development. If you are fully present internally and give your all, there will never be any lulls in the piece. The energy is always there, from the beginning to the end of the piece. Even the pauses are imbued with this energy. You can’t practice something like that on an instrument.

Your work merges meditation music, world music, progressive rock, jazz, and classical elements. Do you consciously shape genre intersections during composition, or do they emerge naturally from your improvisation and experimentation?

The second is the case. The genre transitions arise “by themselves.” However, I don’t call the starting point improvisation, but rather “immediate composition.” This goes deeper than improvisation. When I look inside myself, musical forms emerge that can be assigned to genres.

But seen even more originally, these musical creations simply spring from a musical need for something to ultimately sound more or less like this or that. In that sense, I let myself be surprised by the result. Because there comes a point where you can no longer influence the result with the mind.

It may sound a bit far-fetched, but the most beautiful things, phrases, and sounds always come as a “gift.” You can’t practice that on an instrument. But what you can do is prepare the “ground” (get yourself in the right mood) so that these “gems” come naturally. Usually in an unexpected form. This happens a lot to me, and it is then “complete authenticity” that cannot be influenced mentally. It is contemplative (observational) creating and playing = the result of decades of meditation.

Tracks like “OASIS” and “Cosmic Lila” evoke a strong sense of atmosphere and place. Do you compose with specific visual imagery or environments in mind, or are the destinations more abstract and emotional?

I never compose with images in mind. An image only unfolds once the composition is complete, created by the expressiveness (vitality) in the work. Each listener sees a different image, depending on their individuality—or you could also say that it activates the listener’s mental cinema.

Each composition reportedly takes close to two months to create. What does that extended creative timeline look like in practice — from initial sketches to the final immersive soundscape?

I always proceed in the same way. First, I simply try out different things on an instrument that appeals to me at the moment. As soon as I get an “echo from within,” I dive into it. To do this, I often play a pattern on the instrument for a long time and repeat it daily until this pattern becomes a part of me. Sometimes it can also be a snippet of a melody that emerges, which I also internalize over several days. This becomes the solid foundation on which I then build everything else around it, all with the same dedication and investment of time.

What’s also important is that I take breaks every now and then for two or more days so that I can gain some distance and hear things objectively again. And for the entire work “Unfolding,” I built in breaks of two weeks or more between pieces before continuing. This gave each piece a special identity because it embodies a kind of mini-epoch. It’s very different from if I had created all the pieces one after the other without a break. This also explains the relatively long time frame for the whole thing.

You’ve mentioned decades of meditation shaping your artistic mindset. How does that practice influence the pacing, dynamics, and emotional stillness present throughout UNFOLDING?

It goes beyond the way of thinking. Meditation brings you into a state where everything you do is lived much more intensely. This kind of music would hardly be possible without meditation. It would probably sound good, but it wouldn’t have the depth.

Through meditation, you also learn the immense patience it takes to bring such compositions to life. Every detail, right down to the pauses, must be filled with life. This is achieved by delving deeper and deeper into the creation, playing individual phrases over and over again until they take on a life of their own. The result is a creation with a very high energy level from beginning to end, regardless of whether it is played fast or slow. This “energy behind the notes” gives the work its immersive aspect. One could write a book about this interplay between music and meditation. But I prefer to put these facts into practice, to make them tangible, rather than just writing about them.

If you could collaborate with any artist, alive or dead, who would it be — and what kind of sonic “painting” do you imagine creating together?

This level of detail that I pursue here can only be achieved alone. It’s just like with a painting: a painting can only be painted by one artist; it is his identity, his recognizable signature. When music is on a simpler level, I can definitely perform certain things with other musicians on stage. I’ve done that a lot, especially in the past.

But here this is so extremely distinct and “hyped up” that any small change in direction would result in a loss. It can’t be reproduced on stage. Since I live very much in the present, in the moment, I’m still open if something new comes up in terms of collaboration. It wouldn’t just have to be a good musician, but almost a soulmate.

After compiling over 40 years of experience into UNFOLDING, what’s on the horizon next — new sonic explorations, live interpretations, or entirely new instrumental palettes?

That’s difficult to predict. At the moment, I don’t think I can surpass UNFOLDING. As a perfectionist, I always strive to ensure that new things surpass what came before. I have to let time pass and see if something new emerges. When I play live from time to time, it’s very simple, quiet stuff, so there’s plenty of room to “communicate” musically with the audience. So it is music of the moment, very simply arranged.